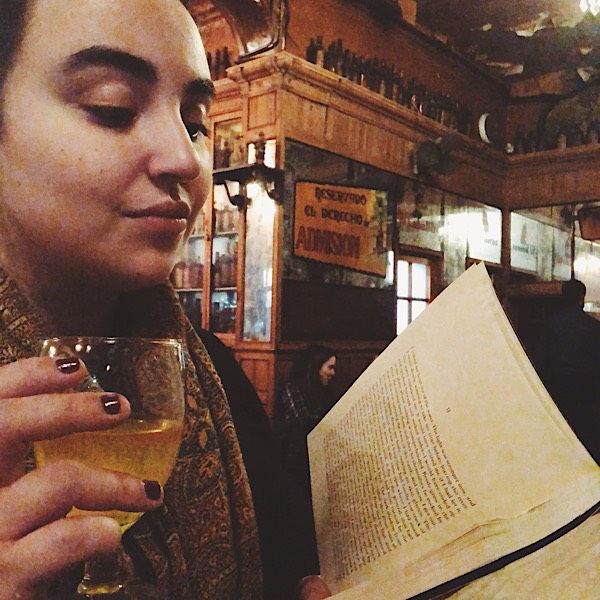

There’s a strange disconnect between the chaotic nature of real life and the consistency that we expect from fiction. Our suspension of disbelief doesn’t extend to certain inconsistencies or “errors” — even when life and our memories are riddled with them. When we’re reading, we expect a certain consistency from the plot, the world, and the characters, that real life does not always comply with. When I visited Barcelona in early 2020 (before the pandemic led to shutdowns), I made a bunch of friends in an unexpected conversation over absinthe at Bar Marsella. All I did was ask if someone had a phone charger, and then before I knew it, I’d been pulled into conversations about Spanish literature and wanderlust. Later that night, all tipsy, we went back to their apartment, and they used my phone to play Lorde and dance, playing one song in particular again and again. Throughout the tough year that was 2020, I played “Supercut” by Lorde again and again. Just the opening lines transformed me instantly back to Spain, to the bold joy of traveling alone and making new friends and falling into their easy, intoxicated friendship circle — the camaraderie of late nights and talking philosophical questions and life purposes with strangers over red wine, broken up by spontaneous dancing in an ex-pat’s studio. A few weeks ago, I was flipping through my travel journal, and I found the entry I’d written the morning after making those friends. In that entry, I wrote that the song was “The Louvre.” I whipped open Spotify, and I turned on “The Louvre.” But it did nothing for me. I turned on “Supercut,” and Barcelona memories blossomed: instantly I could see their studio, taste the wine on my tongue. It wasn’t possible, but nevertheless, there it was, ingrained forever in my story of my trip. My memory itself had made a complete error in the story as it existed according to the facts; but now, the story made sense as my mind had rewritten it. In a fiction novel, this would have been flagged as continuity error. And yet, it makes sense to me. Neil Gaiman writes that fiction has to be convincing, and that life doesn’t have to — life is not expected to follow the rules of a narrative. I’m reminded of many of the tweets that popped up through 2020 that joked that if 2020 was a novel, editors would demand many of the subplots be cut, and suggest that some of the twists were too utterly unrealistic. And yet, 2020 was real, every darn month of it. And yet, I’ve seen readers in workshops critique dialogue or plot turns inspired by real-life situations and circumstances, calling them “too obvious,” “too stereotypical,” or “too much.” Readers will say that a character’s choice didn’t work because “they wouldn’t do that,” as if real people don’t make irrational choices every day. Dialogue peppered with the “like” and “um” and “you know” of our day-to-day dialects becomes nearly impossible to read for most readers once thrown into a novel. — Caleb Roehrig (@MikalebRoehrig) May 2, 2020 Why is it that we expect of fiction what we can’t expect of the world? Why is it that it’s hard for us to immerse ourselves into a world that has these real-life corollaries? The simple truth is, when we are reading, we are aware of the object in our hands, whether it be concrete — its pages turning, its cover firm — or on our ereaders or audiobook playlists, counting down by percentage. It is a thing that ends. It is a thing that was crafted. We don’t necessarily engage the author at every turn, but we are always engaged with the object-ness of a text. Each book becomes an object in our mind, and that means it has boundaries. It has a limit to what it can hold. Our world is wide, open, and chaotic. There are few limits to it, and the ones that are there are often so big or so abstract that we cannot see or comprehend them fully. But the text is an object that we hope to consume. It has a beginning, and so we know it will come to an end. There will be a final page. And as a result, we view a book less as the “real world” and more like a hiking trail that is meant to bring you into the forest and bring you out of it. The trail might take unexpected turns; it may twist around on itself; it may falter out and then return — the story itself may surprise you, and you could leave this path confused, happy, satisfied, sad, unsettled, or anything in between. But there will be a path, and there will be an ending. Life has no such foreknowledge, or rarely does. You do not know when a relationship will end, or whether it will end at all. We know life will end, but death is abstract and we have no idea what percentage or page we’re on. It’s only in aftermaths that life takes on comprehensible narrative, and it’s applied only in that retrospective, storytelling gaze — the same gaze we expect from an author. When I journaled of my time in Barcelona, my mind created a continuous tale of my day that ended at my new friends’ apartment. It included the absinthe, the Lorde, the walk to their studio. It omitted the awkward first sentences, the waffling I did over whether I should skip Bar Marsella, the drips of wine that may have run over my hand and onto my skirt. None of that was part of the narrative as I remembered it. And yet my arrival itself at Bar Marsella, my phone dying, that became part of the story of how I ended up at their apartment, folded into a continuous narrative. When there is an end to a story, a narrative can form. In our lives, we often don’t know when things have ended until they already have done so. Only then does a relationship, a memory, become an object that’s contained and has a beginning and ending — in retrospect, everything built up to the breaking point of a relationship; in retrospect, there were signs. We author those stories about ourselves, and life in retrospect takes just a little more believability. And when we pick up a book, we know it will end, and we know exactly when — in 230 more pages, or in three more hours — and so we expect the author to have already infused it with some level of continuity. We expect a path. In our strange way, we are always seeking a continuous narrative for ourselves. And so when we pick up a book, which we are consciously aware is meant to be a complete narrative, we have little patience for the small continuity errors of day-to-day existence. We want the story.